Search powered by Funnelback

Want to read all blog posts in this series? We start with an assessment of what we think is the new age of digital business problem solving in part 1, to then discuss how to tackle functional fixedness in part 2. In part 3 we dive into the future of search and whether it's proactive.

Natural language question answering (NLQA) is an exciting and challenging growth area for web and mobile search. It arises predominantly due to the quick uptake in voice search services such as Siri and Cortana. Anticipation for its development is building, which means its impact at an enterprise search level is also well worth investigating.

Search by NLQA involves asking a question in a conversational way, such as “who was president of the USA when the Vietnam war ended?”. This style of querying tends to come easily when using voice-activated search services or virtual digital assistants. It is sophisticated when contrasted with the approach used by the majority of web, site or enterprise search queries processed to date: keyword searches.

In certain circumstances though, it would be sensible to question why a simple keyword search should need to be expanded to a natural language query, particularly if the user is typing on a mobile, as we know the majority of our digital consumption now takes place on mobile (51% compared to 42% for desktop). NLQA requires more words which when typing, means more time, more effort.

This is of particular interest if the keyword search and the natural language query return the same information. If you were trying to remember the name of a particular movie for example, and you entered a keyword search of ‘Harrison Ford 1993’, a Google web search will return a top of result for the Wikipedia page for the movie The Fugitive, and a second result for the IMDB page for the same film. At a glance you have the information you need, as captured in the search result summary, and if you’re now intrigued to see the cast list, you can click through the first result to find it.

So, why should you have to expand your query to “What is the name of the film starring Harrison Ford made in 1993?” Perhaps the answer lies in the context or sentiment that the additional words add to the query, which possibly changes the result set to include a Google ‘featured snippet’.

Could catering for NLQA within enterprise search be worth our while? More importantly, can we assume that people prefer a natural language query?

Out of curiosity, we ran a small test over Funnelback query logs for a sample of our website search customers, which included over 272 million queries. Out of all the queries, only 0.1%, or 1 in 1000 queries, were identified as being input in ‘natural language’. And although we don’t have the same test data for enterprise search, the use case for natural language query processing within an enterprise seems to be thin. With such a small percentage of queries being posed this way, could focusing on the answering of the query, regardless of the input method, be a more productive way of addressing and improving site and enterprise search user experience?

How you answer the question is more important than how the question was posed

The popularity of NLQA is most certainly on the rise. Users are excited at the prospect of treating their device, and in this case specifically their search interface, as an almost human-like interaction.

Our vision is to make discovery of information more intuitive and immediate than asking an expert. In essence this means that question answering with or without the natural language query is a broader and important use case in itself, because we know that if the question is not answered accurately, your are likely to lose your web site user to a Google web search, at best. At worst, in an enterprise scenario, time and resources (money) will be spent recreating the information they need.

We predict that the business impacts of focusing on impactful question answering could be as far-reaching as:

- Enhanced user experience for any and all industries

- Decreased phone enquiries in a call center environment

- Decreased website maintenance costs overall

- Decreased spending in digital transformation strategy implementations

- The ability for organizations to promote key business offerings, such as events, courses, programmes.

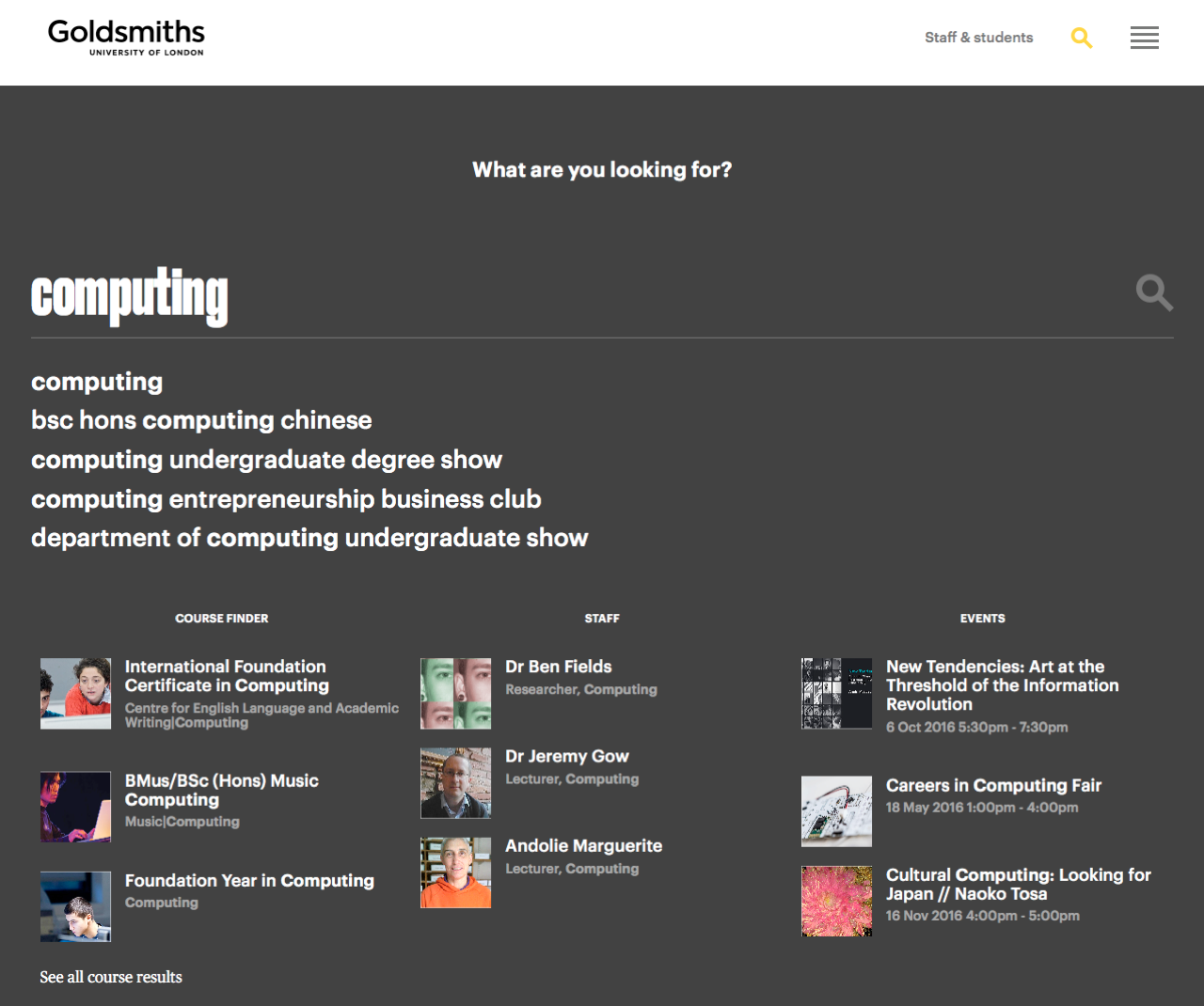

Achieving this experience requires effort and planning. Still, patterns naturally emerge from your data which provide a logical place to start dividing content into categories, such as staff databases. Or, in a university environment, a course or events database. In a federal government department scenario, the events and staff search are just as relevant, but what about grouping policy documents together, or employee support services? Is there a use case for incorporating results from your company YouTube, Twitter or LinkedIn channels?

As usual, we’re interested in how we could take this even further. An organization that chose to influence which content items are returned based on each user's location, organization or search history, could provide a search experience that is personalized, anticipating the user's needs and possibly resolving them before they complete their search query.

By providing a well designed, contextual and highly visual alternative to 10 blue links on a search results page, we can effectively answer the question posed by the user, eliminating the need to scroll through search results and in some cases (with some clever results summaries displayed) the need to even click through to a page. This approach is stylish, but more importantly, it considers the premium on your customers, your employees, and eventually your business’ time.